CLICK FOR INFORMATION: The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS)

MECHANISMS OF WEIGHT LOSS

Reduction of caloric intake plays an important role in the dramatic weight loss produced by bariatric surgery. However, this is only partially attributable to a reduced capacity of the stomach or pouch. Many patients report a subjective decrease in appetite and increase in postprandial satiety after surgery, which helps them maintain lower intake of food. This experience suggests that the effects of bariatric surgery on weight loss and comorbidities may have neuroendocrine mechanisms, and are entirely attributable to mechanical restriction of food intake or of malabsorption.

Emerging data suggest that alterations in neuroenteric hormones that regulate appetite and energy expenditure could contribute to changes in satiety after surgery. Several studies have demonstrated an increase in postprandial total peptide YY concentrations (both PYY and PYY3-36) after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) compared with lean or obese nonoperative controls . This postprandial increase in PYY is not reported after an adjustable gastric band (AGB) . However, a single series of 12 patients undergoing the vertical banded gastroplasty (also purely restrictive) reported an increase in fasting and postprandial PYY concentrations after surgery to levels comparable to concentrations measured in lean controls

In addition, bile acid signaling, mediated through the farnesoid-X-receptor (FXR), appears to be integral to achieving the weight loss and beneficial metabolic effects of sleeve gastrectomy (SG) in rodent models of bariatric surgery . Studies in adults have also demonstrated a rise in circulating total bile acids after RYGB, and to a lesser degree after SG; however, no significant change was demonstrated after AGB [46,47]. Bile acids have also been shown to rise significantly in adolescents as well during the rapid weight loss phase in the first three months after SG.

Dramatic improvements in insulin resistance and diabetes occur after RYGB, even prior to any significant weight loss. These changes may in part be due to increased secretion of incretins, such as glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP-1) by intestinal endocrine cells after surgery . After RYGB, postprandial GLP-1 plasma levels rise dramatically compared with levels in lean and obese controls, and compared with patients undergoing AGB . F

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/surgical-management-of-severe-obesity-in-adolescents?search=pediatric%20obesity%20surgery&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1

Recommended Evaluation:

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure

Waist circumference

Weight

Height

Tanner Stage (criteria for surgery is Tanner stage 4 or more)

Laboratory testing

Fasting lipid profile

Fasting insulin and glucose

Oral glucose tolerance test

Hemoglobin A1C

Liver profile

TSH

Diagnostic evaluations

Polysomnography

Echocardiogram

Electrocardiogram

Urea breath test or endoscopy to exclude helicobacter pylori infection

Bone age if needed to assess skeletal maturity (criteria for surgery is attainment of ≥95 percent of predicted adult height)

Comprehensive psychological evaluation

Evaluation by pediatric psychologist or psychiatrist to screen for cognitive and psychiatric disorders, assess emotional maturity, decisional capacity and family support

Waist circumference

Weight

Height

Tanner Stage (criteria for surgery is Tanner stage 4 or more)

Laboratory testing

Fasting lipid profile

Fasting insulin and glucose

Oral glucose tolerance test

Hemoglobin A1C

Liver profile

TSH

Diagnostic evaluations

Polysomnography

Echocardiogram

Electrocardiogram

Urea breath test or endoscopy to exclude helicobacter pylori infection

Bone age if needed to assess skeletal maturity (criteria for surgery is attainment of ≥95 percent of predicted adult height)

Comprehensive psychological evaluation

Evaluation by pediatric psychologist or psychiatrist to screen for cognitive and psychiatric disorders, assess emotional maturity, decisional capacity and family support

Contraindications for surgical weight loss procedures in adolescents include:

●Medically correctable cause of obesity

●An ongoing substance abuse problem (within the preceding year)

●A medical, psychiatric, psychosocial, or cognitive condition that prevents adherence to postoperative dietary and medication regimens or impairs decisional capacity

●Current or planned pregnancy within 12 to 18 months of the procedure

●Inability on the part of the patient or parent to comprehend the risks and benefits of the surgical procedure

●Medically correctable cause of obesity

●An ongoing substance abuse problem (within the preceding year)

●A medical, psychiatric, psychosocial, or cognitive condition that prevents adherence to postoperative dietary and medication regimens or impairs decisional capacity

●Current or planned pregnancy within 12 to 18 months of the procedure

●Inability on the part of the patient or parent to comprehend the risks and benefits of the surgical procedure

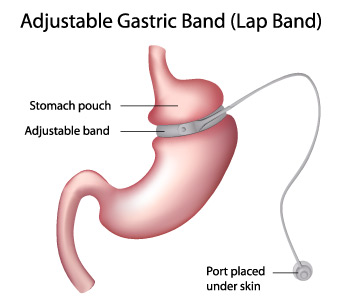

Adjustable gastric band

Adjustable gastric banding (AGB) is a purely restrictive procedure that compartmentalizes the upper stomach by placing a tight, adjustable prosthetic band around the entrance to the stomach . The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two AGB devices for use in adults in the United States, but these devices are not FDA-approved for adolescents younger than age 18. Numerous retrospective studies of adolescents have been published with favorable results, although the weight loss achieved is probably less than for SG and RYGB. Lack of FDA approval and the increasing trend for use of SG has resulted in rapidly declining use of AGB in adolescents, so that it now represents 1 percent of all adolescent bariatric procedures.

Sleeve gastrectomy

The sleeve gastrectomy (SG; also known as vertical sleeve gastrectomy) is a partial gastrectomy, in which the majority of the greater curvature of the stomach is removed, creating a tubular stomach The frequency of this procedure for weight loss surgery has been rapidly increasing, and it accounts for approximately 80 percent of bariatric procedures in adolescents. It was originally performed as the first part of a two-stage weight loss procedure for high risk extremely obese adults, but because it often achieves excellent weight loss outcomes, it is now often used as a stand-alone procedure . Data on very long-term outcomes is pending.

Because SG is less complex than RYGB and has a lower theoretical risk of micronutrient deficiencies, it is an attractive option for adolescents.

Additionally, if patients regain weight in the long term, the SG can be converted to a RYGB. Outcomes for weight loss and comorbidity improvement are generally excellent, although the long-term weight loss may be less than for RYGB, at least for a subset of patients. Compared with AGB, SG has the advantage of avoiding a foreign body and potential associated complications.

SG may be a particularly appropriate choice of procedure for individuals with cognitive deficits, younger age, or other issues that might increase risk for postoperative nutritional deficiencies. However, outcomes for these special populations remain unclear because the only information is from very small case series with several years follow-up.

In a sleeve gastrectomy, the majority of the greater curvature of the stomach is removed and a tubular stomach is created. The tubular stomach has a small capacity, is resistant to stretching due to the absence of the fundus, and has few ghrelin (a gut hormone involved in regulating food intake)-producing cells.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) creates a small (less than 30 mL) proximal gastric pouch that is divided and separated from the distal stomach and anastomosed to a Roux-limb of small bowel 75 to 150 cm in length . The surgery has been the most commonly performed bariatric procedure in the United States until more recently, but now accounts for approximately 20 percent of procedures in adolescents.

The long-term outcomes for weight loss and comorbidity improvement are well established for RYGB, based on more than 25 years of experience with this procedure in adults. In addition, it has particularly dramatic benefits on glycemic control, which may offer some advantage for patients with type 2 diabetes . On the other hand, there are probably more risks for nutritional deficiencies compared with SG. In particular, iron sufficiency and long-term outcomes for bone health after RYGB are not well studied.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

This figure depicts the stomach's appearance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, which creates a small stomach pouch by dividing the stomach and attaching it to the small intestine. The pouch is only able to hold about an ounce of food, causing a feeling of fullness after consuming a very small amount; over time, the pouch stretches to hold about one cup. In addition, the body absorbs fewer calories since food bypasses the majority of the stomach as well as the upper small intestine (duodenum). This intestinal arrangement (Roux-en-Y) seems to cause decreased appetite and improved metabolism by changing the release of various hormones.

Other SURGERIES — In the past, the range of surgical weight loss procedures performed on adults and a few adolescents included jejunoileal bypass (a procedure associated with a high rate of malabsorptive complications), vertical banded gastroplasty, and banded gastric bypass. Due to unsatisfactory safety profiles and/or efficacy, these procedures are no longer recommended. Other procedures that cause malabsorption, such as biliopancreatic diversion, are occasionally performed on adults but are generally not recommended for adolescents due to lack of safety data in this age group and concerns about long-term nutritional complications

https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/service/bariatric-surgery